|

|

October 29, 2001

Daily horrors of the Jim Crow era recorded in oral history project

By Jennifer McNulty

For historians, few projects offer the professional or personal satisfaction that

comes with gathering and preserving little-known stories. And so Paul Ortiz, an assistant

professor of community studies, feels particularly honored to have been part of a

major project to record the oral histories of African Americans who lived under Jim

Crow in the segregated South.

|

| Paul Ortiz, an assistant professor of community studies, was research coordinator

for the oral history project and conducted dozens of the field interviews. |

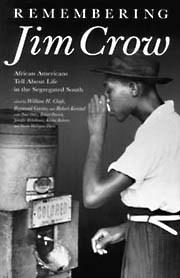

The highlights of those oral histories have been compiled in the important new book

Remembering Jim Crow: African Americans Tell about Life in the Segregated South

(New York: New Press, 2001).

The book, illustrated with 50 rare segregation-era photographs, is accompanied

by two CDs: One contains excerpts of the original interviews and the second is a

major radio documentary produced by American RadioWorks that will air on many National

Public Radio stations on November 13.

The book's firsthand accounts of living under Jim Crow convey the hardship and suffering

experienced by African Americans in the United States from the end of the 19th century

into the 1960s.

Participants describe the daily horrors of lynching, harassment, and sexual exploitation,

and they reveal the resourcefulness with which they fought back, building communities

at home, at work, and in the church to resist oppression and lay the groundwork for

broad social change.

Ortiz, who was research coordinator for the project and conducted dozens of the field

interviews as a graduate student at Duke University, edited two of the six chapters

of the book, "Heritage and Memory" and "Work." Other chapters

address "Bitter Truths, "Families and Communities," "Lessons

Well Learned," and "Resistance and Political Struggles." The publication

is a project of the Behind the Veil Project of Duke's Center for Documentary Studies.

Ortiz found particular inspiration in the stories of Leon Alexander and Earl Brown,

both of whom organized coal miners in Alabama in the 1930s in a struggle to unionize

for better wages and working conditions--a goal that encompassed getting white miners

to join the union, too.

"We know how tough Birmingham was in the civil rights era," said Ortiz,

who studies social movements. "Imagine how tough it was in the 1930s. These

men fought the system without any national attention or support or anything we associate

with the civil rights movement of the 1960s."

Interview subjects were eager to relate their life experiences--after Ortiz and his

fellow interviewers built trust.

"These senior citizens are at a point in their lives where they really want

to tell their stories," said Ortiz. "They share a sense that they made

history, and they feel they can educate the younger generations."

Researchers gained the trust of participants in part by explaining their intention

to contribute a full set of tapes and printed materials to community repositories

in regions where they conducted interviews. More than 1,200 interviews were recorded

between 1993 and 1995.

"There is a renaissance of public history around the country, and community

historians were very helpful to us," said Ortiz. "We wanted to link the

academic and community components of the project."

Jim Crow was one of the longest periods of American history, yet historians have

done a poor job of documenting the actual experiences of black Americans during the

age of segregation, according to Ortiz. Unlike slavery, which had a definitive end,

and the civil rights era, which marked a period of "positive and uplifting progress,"

the segregation that was pervasive under Jim Crow lingers today, said Ortiz.

"I can't go before a class of sixth graders and tell them segregation is over,"

he said. "They would laugh."

Oral history is an exciting and challenging tool for historians, said Ortiz, in part

because interviews invariably wander into unexpected territory.

"I remember talking with Tolbert Chism about Native American, African American,

and white interrelationships, and he started talking about the Trail of Tears,"

recalled Ortiz, referring to the forced removal in the 1830s of Native Americans

from the East Coast to the Oklahoma Territory in which thousands died. "I nearly

dropped my notebook. He traced his heritage back to the Trail of Tears."

Accounts of racial violence and sexual exploitation were "incredibly painful"

to hear about, but Ortiz said the saddest aspect of the project for him personally

was the "vivid descriptions of everyday racial oppression--the sense of being

in a system that's not of your own making and being kept trapped at the bottom of

society."

The struggles of black farmers in south Florida were anguishing, he said, as they

were thwarted in their repeated attempts to gain ground by planting their own crops,

buying land, and sending their children to school. "The whites would burn the

crop, shoot the farmers, and shut the schools at harvest time," said Ortiz.

"It's the cumulative oppression that gives you the sense of anguish."

And yet the book is hopeful, too, in a way that reflects the full range of human

experience. Out of their oppression, individuals came together and formed unions,

church groups, and fraternal organizations that have endured and are still thriving

today. They learned, as Ortiz put it, "how to build a democratic society in

an antidemocratic society."

"Without half the advantages we have today, these people decided not to accept

the status quo," marveled Ortiz. "People will read this and begin to feel

a deeper appreciation for the role ordinary people can have in affecting social change."

The book was edited by William Chafe, Raymond Gavins, and Robert Korstad with Ortiz,

Robert Parrish, Jennifer Ritterhouse, Keisha Roberts, and Nicole Waligora-Davis.

|

|